WHY DID 800 (OR MORE) PEOPLE TURN UP AT THE BALLARAT TOWN HALL on 21 April 1937

Courier, 22 April 1937 ‘Lively Debate on the Spanish Question”

On 21 April 1937, a crowd of more than eight hundred turned up at the Ballarat Town Hall. They were there to debate the merits of the Spanish Civil War, on the other side of the world; not so much to debate but to make clear which side they were on!

The Courier in their report of the meeting remarked that: “If there were any who supposed that the protracted correspondence in the “Courier” concerning the situation in Spain had left the general public a little weary on the subject, the attendance at last night’s debate at the City Hall would have come as a startling surprise. Long before eight o’clock the hall was packed full and the partition between it and the concert hall was thrown open. By the time the debate began the crowd stretched most of the way to the far wall.”

Many first–hand accounts of the meeting are contained in a set of tapes made by the Ballarat Library in 1982-3 as part of a project ‘Ballarat and District 1920-1940 An Oral History’ and even thirty years later the memories were vivid and consistent. Father McInerney, later to become a Monsignor described how he had developed a group within the CYMS (Catholic Young Mens Society) who were ambitious for higher things, they were deeply interested in the teachings of the church and they wanted to go more deeply into the actual teachings and to read around those subjects. Among the leaders were John Larkins, a budding solicitor, and Jack Sheehan who later became Minister for Housing in the 1955 Cain Government and they made themselves as conversant with the church and especially with the church’s attitude to questions of the day that they undertook to give public lectures on relevant questions in St Patrick's Hall. So when the opportunity came to debate the merits of the Spanish War with Trades Hall they were ready.”

Monsignor McInerney recalled

The Communists, by the way, were successful in locking the doors so that their protagonists could be the first in and get the front seats. But the C.Y.M.S outwitted them by getting through the window and they occupied these first seats.

Beau Williams, one of the speakers on behalf of Trades Hall said that

the Catholic group marched the senior students from St Patrick’s College down and they took the front of the hall…. Other Catholics were bussed in from outlying agricultural districts. … bringing all sorts of weapons…bike chains and so on.”

B.A. Santamaria often attributed the awakening of his interest in politics to the 1937 Melbourne University debate held some weeks before the Ballarat debate, in which the Spanish Civil War and the clash of values it represented for Western civilisation was highlighted. The young Manning Clark, in the audience that day, would also later remark how this debate first illuminated for him the two competing beliefs and value systems between which he would waver – that of traditional Christianity and the rationalist ideologies born of the enlightenment. In his autobiography The Quest for Grace, he likened the atmosphere, even before the combatants entered the room, to being in the outer at a Carlton-Collingwood Aussie Rules game. The Melbourne debate in an academic setting attracted a large crowd between 1000 and 1500, of whom two- thirds were Catholics. The Ballarat debate was organized within the community and much more a broadly based event.

The Rise Of Fascism In Spain

In 1931 a Republic had been declared in Spain when the centre left Republican government of Manuel Azafia gained power. In a desperately poor nation, almost feudal in its social structure, the government introduced radical agrarian reform and disestablished the powerful Catholic Church. After a brief period of conservative power in 1934, the Left returned to power in the election of 1936. The Spanish Africa army in Morocco rebelled against the government and was transported to Spain by Italian and German aircraft creating a civil war between the republicans, who were loyal to the democratic, left-leaning and relatively urban second Spanish republic versus the nationalists, a largely aristocratic conservative group led by General Francisco Franco.

Beleaguered Spain became the focus of idealists around the world, including sixty Australians, who joined the International Brigade to fight Fascism and to preserve the Republican government.

One of those was Kevin Rebbecci who had a noteworthy Ballarat connection. The Rebbecchi family history tells that he was only 21 when he died, unable initially to be accepted into the International Brigade due to his Italian/Catholic background. He crewed on blockade runners running food into Spain. On his last trip their ship was bombed/shelled at Bilboa and they had to run it aground as it was sinking. He did then join a brigade and was machine gunned in the legs during the Ebro offensive in July 1938, and then badly injured when a mule rolled on him while being evacuated during the night. He was very knocked around and with little medical care died of yellow jaundice at Vic, 60 kms from the French border, on New Year’s Day 1939. His family have recently identified his grave. His family came to Australia during the gold rush in 1850, part of the Swiss/Italian diaspora who settled in the Central Highlands, and were involved in the Eureka Stockade. His original ancestor Antonio married Peter Lalor’s cousin, Margaret Masterton immediately after the uprising. Kevin’s father was a prominent trade union official in Melbourne, a founder and Secretary of the Federated Clerks Union and was one of the founders of the Australian Council of Trade Unions.

Why Did So Many People Care?

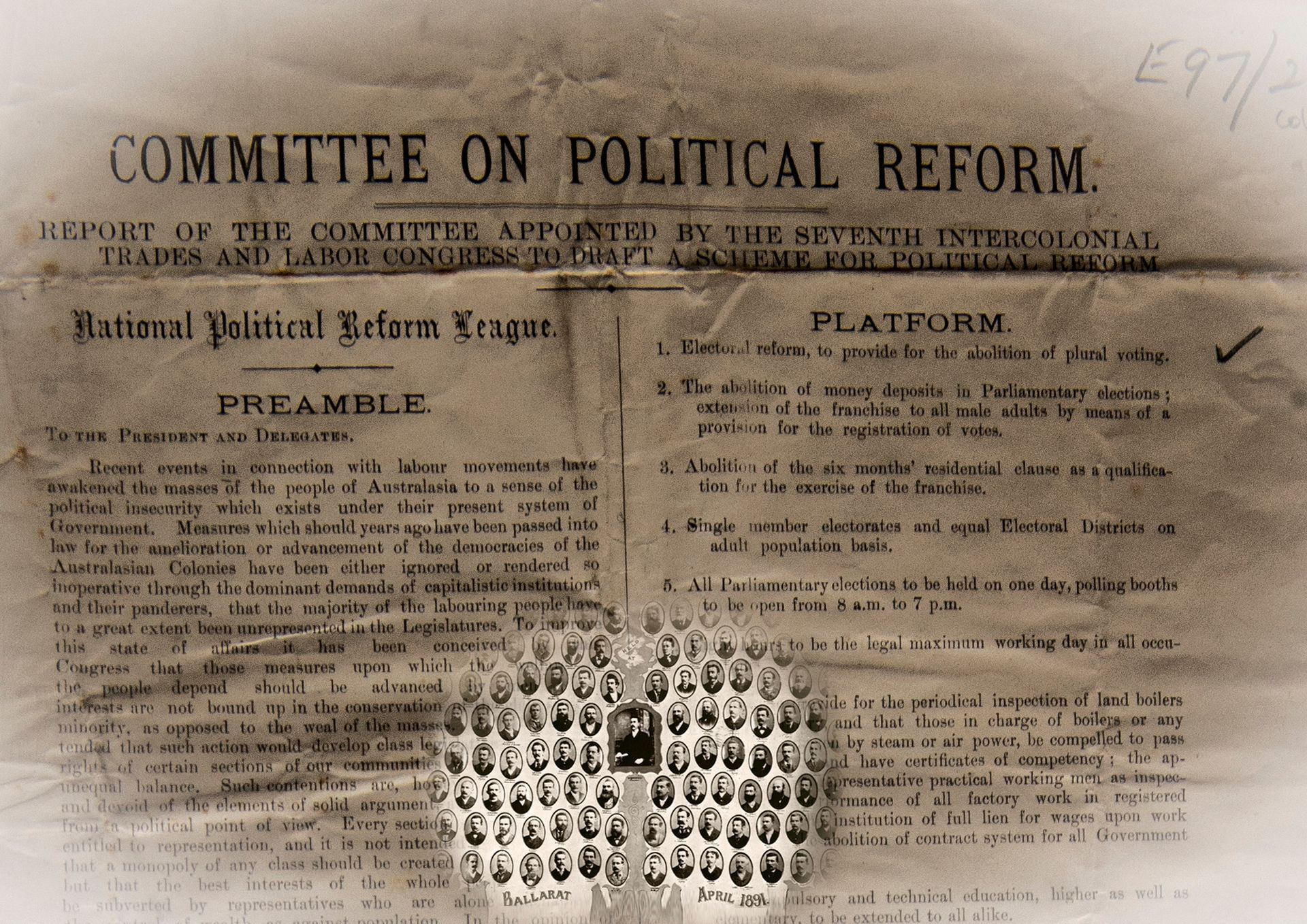

In Australia, after World War 1 and the Russian Revolution, communism during the 1920s began to attract followers, while within the Catholic church the fear of communism had been emerging from the 1890’s, at least going back to 1891 when Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical, Rerum Novarum, “Rights and Duties of Capital and Labour,” addressed the condition of the working classes and discussed the relationships and mutual duties between labour and capital, as well as government and its citizens. It supported the rights of labour to form unions, rejected socialism and unrestricted capitalism, whilst affirming the right to private property. In Australia, however the reality was that communism during the 1920s was no more than a minor irritant on the periphery of the labour movement- though this altered in the 1930s as a consequence of the Great Depression. Antagonism between the two competing systems of beliefs, Catholicism and Communism, would increasingly pull at the right and the left of the labour movement.

In the 1930’s Spain became that battleground for the two contending ideologies - Christianity and Communism. The supporters of this Civil War used all the new communications technology of the Twentieth Century. Motion pictures, posters, books, radio programs and leaflets were all very influential during the war. We may think social media is a new phenomenon in the political space, but a film “The Spanish Earth” co-produced by Ernest Hemingway and Lillian Hellman which premiered in America in July 1937 was dramatically used to advertise Spain's need for military and monetary aid, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt invited Hemingway to show the film at the White House in advance of its premiere. At the same time Pablo Picasso’s painting ‘Guernica’ heralded as the most Important symbol of peace and the horror of war in the 20th Century was featured in the1937 International Exhibition in Paris. Taking inspiration from the destruction of Guernica by German bombers, an unarmed Basque (and Catholic) township, the work's size (11 ft by 25.6 ft) grabbed much attention and cast the horrors of the mounting Spanish civil unrest into the global spotlight.

The Australian Catholic Truth Society published more than three hundred thousand pamphlets on the conflict in Spain in 1936 alone, detailing tales of slaughter and carnage exacted against the church.

Looking back in 2007, Eric Hobsbawn in “The Guardian” wrote that ”In creating the world's memory of the Spanish Civil War, the pen, the brush and the camera wielded on behalf of the defeated have proved mightier than the sword and the power of those who won.”

This certainly was not apparent to the combatants fighting it out in Ballarat in 1937. For them the Spanish Civil War was ‘a war to the death between two hostile ideas of life,’ and both sides were at least agreed on this

The Spanish Civil War Erupts in Ballarat

Shauna Hurley has an excellent chapter “The Red and the Purple” in her thesis “Catholics, Communists and Fellow Travellers” about this period in Ballarat’s history. She asserts that the Spanish Civil War served to deepen the bitter conflict on both personal and institutional levels.

The Spanish Civil War issue first erupted in Ballarat in 1936, when most Trades Hall Councils, including Ballarat, passed resolutions condemning the fascist forces’ attempt to overthrow the Republican government .‘Franco and the Catholics against atheistic communists’ or ‘the democratic people of Spain against international fascism.’

At Ballarat Trades Hall Council meetings on 29 September and 8 October 1936, the council offered moral and financial aid in support of the ’heroic struggle of the Spanish people against fascism and its bestial Moorish murderers.” A similar resolution was later passed by the ACTU. E W Peters, State President of the ALP. soon bought into the debate.” He attacked the Ballarat Trades and Labour Council because of their support for the Republican government and the Ballarat Trades and Labour Council carried a resolution attacking Peters for his attitude.

The Melbourne Trades Hall Council disassociated itself with the statement of Peters by a vote of fifty-one votes to forty-one. Just prior to this, it was recorded in the Courier on Monday, 5 October 1936 that-

On Sunday 4 October, Bishop Foley ascended the pulpit at the conclusion of 7 o’clock mass at Ballarat’s St Patrick’s Cathedral and denounced the TLC resolutions. He concluded, “You men before me and those of you in unions said to have been represented at this (TLC) meeting… will not allow your money to be used for the purpose of subsidizing savages.”

Bishop Foley’s intervention was followed by numerous letters to the Editor of ‘The Courier’, until by March 1937 there were at least two every day from regular writers such as: ‘See Things As They Are’, “Student of Recent Events”, “Democrat”, “Campion”, and those who decried pseudonyms such as Ted Rowe, Beau Williams, C.A. Russell, J.Conlon (an Inspector of Catholic schools in the area)), J J Walsh, Gerard Sherry (whose father ran a business at the Catholic bookstore in Bridge Street)[1], A Cleary and D.S. Spero. “The age-old division of a decaying ruling class fighting against the slave class attempting to gain its freedom” versus “anarchy and ‘godless barbarism” were consistent themes.

As well, Tom Hollway the local member for Ballarat, first for the UAP then the Liberal Party, and who would later become the Liberal Country Party Premier in 1947-8 and 1948-50, had given an address to Ballarat Rotary in February 1937 which was reported in the “Courier”. Hollway was quite certain that Communism was obtaining too great a hold on Ballarat. With regard to Spain he said there was a conflict between the rebel or Christian forces and the socialistic and communistic forces of the present Spanish Government. He thought that conflict had to some extent been limited, and there was a reasonable prospect of at least temporary peace in Europe.

The Great Debate

At Trades Hall, they decided to throw down the gauntlet to Hollway and on March 19, 1937 Ted Rowe gave a public address on the Spanish Civil War to a well-attended meeting. The subsequent debate was the culmination of a challenge by the Campions to the Trades Hall extended in the ‘Courier’. The proposition was “That the Spanish Government is the ruin of Spain” with speakers for the motion being Jack Sheehan and Stan Ingwerson who had taken the same side in the Melbourne University debate, and speaking against Ted Rowe and Beau Williams. Jack Sheehan, just a young man, but also to go on to be a major ALPr figure in Ballarat for another twenty years, and whose office when he was Minister of Housing in the Cain government was in the Ballarat Trades Hall, on this night was on the opposite side in the battle of ideas.

Memories of that night lived on. These recollections from interviews with people who were there that night who still remembered it vividly in 1983.Bert Williams who worked at the Ballarat North Workshops said –

Ted Rowe was debating Communism…. and Beau Williams, they both worked at the workshops. Billy, little Billy (W.A. Prowse), he was the chairman anyway. It was packed out at the City Hall. The scare of Communism here.” Monsignor McInerney, organiser of the Campion society said “The Campion's, and to some extent the C.Y.M.S. were, naturally, pro Franco in this fight against what was quite obviously Communist infiltration. At the same time, especially centring in the workshops in North Ballarat, there was quite a dynamic group of Communists led by Ted Rowe who later gained a certain Australia- wide fame as a leading Communist.” Beau Williams, referring to the call by Ingwerson at the beginning of the debate ”Viva Christo Re (Long Live Christ the King)” found’ “the scene from the platform at this call…indescribable, the majority of the audience rose, screaming, and shouting.

In 1983 looking back, John Bongiorno, local fruiterer and Ballarat Catholic identity summed it up -

A lot of water has flowed under the bridge since then, but in those days it was all ”black and white". You were either a rabid Communist or a devout Catholic, and some people felt very, very strongly. Spain was still seen as far away, and it would be a place where you could recommend rain to go to, rather than something that involved us in Ballarat.” has a tone of bemusement about it still thirty years later.

It was a very good debate that memorable night, and the Town Hall was packed. It aroused a lot of interest. That was a world event that shook Ballarat. I don't think that it led to much acrimonious discussion…Chiefly amongst people who read however. I would have been about 26 or so then, and certainly it was argued about at the workplace, mainly between Catholics (they were called fascists) and Communists, and their "fellow travellers.

We were told stories (and they were probably true), that nuns were being raped and bayoneted, and priests were crucified on the steps of their own churches. It was a sticky situation over there, but it seemed a long way away, and I suppose only people who read and kept abreast of the world events would have been deeply moved by it. Well, you see it was the Campion society, intellectual laymen who represent the church. Some people would still remember the Campion Society, a group of intellectuals based in the Melbourne University. There was Bob Santamaria, one of the chief instigators of the Campion movement, and they did build up a strong defence of the Catholic Church. Belloc, Chesterton, Waugh, Martindale, were our heroes. The arch enemy in those days was the Communist. These people were genuinely hungry for social justice. With some reason, they argued that the old church was equally as guilty as the Capitalist, were in league with them, and had been exploiting the workers. No one today would deny that. The church had not yet experienced Vatican II, the windows and doors of the church were still tightly locked against "the world the flesh, the devil", and the landless, exploited people. It was the dynamism of the ‘commo’ activist who eventually provoked a Catholic reaction.

Jack Sheehan recalled

I got a shock when I walked into the City Hall that night to see the size of the audience, overflowed right into the main hall. Also the Chairman was a chap W.L. Prowse, a very diminutive bloke. My first statement to one of the supporters was, “Can this bloke control this crowd?” Well, Prowse is now ninety years of age, over 90 and ‘till last year he had one of the most resonant voices you could ever hear. He was the same that night. He was a much younger man, much younger, but he held that audience. No nonsense about him as chairman. Only for him is the thing would have been out of hand.

Sheehan, not then a member of the Labor Party, summed up his opponents in the following way, and, as many others did remarked on Ted Rowe’s previous allegiances-

Williams was a much more moderate speaker than Rowe, more balanced, more reasonable man, but he believed in his cause. Rowe was a real mob orator…I think you’ve got to admit that there was atrocities on both sides. But I felt Franco’s cause was right. It was too dangerous for us as a Western Nation to risk another –ism (any -ism is the same, tarred with that one brush), allied to Nazism and Fascism. If Spain had have gone at that stage when the World War Two, Hitler was planning for that, was about to break out, you would have had a frightful situation, in the early days with Russia, Germany, Italy and Spain…I was about twenty-one. Of course Ingwersen was only about twenty-three or four. Rowe and Williams were mature men, well, I thought that, but they were young men then. Rowe incidentally, had been a C.Y,M.S. man. He was a very able little codger. He understood Marxism at a greater depth, I think, than many of his colleagues.

The deepening rift in the labour movement in Ballarat between the largely Catholic right-wing and the left wing was noted by Beau Williams.

The entry of Bishop Foley into the controversy had a tremendous effect on the Catholic Community in Ballarat and a large influx of Catholic members to Branch Meetings of the union took place. They were highly organised and were intent on electing delegates to the Trades and Labour Council. This happened in other areas throughout Australia too, but this, in my estimation, was the first development of Catholic organised attendance at Union meetings for the purpose of having a policy of the Catholic Church adopted by the Unions. This, I think, was the beginning of what later became Catholic Action which later became the Movement under Santamaria and the Industrial Groupers as they carried their policy into the Labor Party.

But the rift was felt at many levels. John Curtin, elected as federal ALP leader in 1935 maintained the ALP’s strictly non-interventionist policy towards Spain, as he believed if he “said anything about Spain he might split Labor from top to bottom.”

Appeasement

The broader context, of course, was the fear of war and an eagerness to appease Germany, Japan and Italy, shared by all the major parties. The government gave very strong support to the appeasement policies of the Chamberlain government in London regarding Germany.

Beau Williams made it clear what he thought of the appeasement argument.

The average person in Ballarat, who was a non-Catholic wasn't much impressed by it, by what was happening, They didn't understand this was to be the training ground for the Hitler and Mussolini forces to be used later in a world war, … and there was a policy of non-intervention are far as many of the powers of the world were concerned. There was always I think, as far as the governments were concerned, the hope that there would be war and if war was to break out it was to be between the Fascist powers and the Soviet Union. That was the main direction in which they were all trying to push the war, so they placated Hitler and Mussolini…. The idea was to placate them in the hope that they would ultimately vent their spleen and turn the whole of their forces against the Soviet Union and that, as far as the Western world was concerned, would have been a very good war. But it just didn't work out that way. I mean they built up the forces of Hitler and Mussolini, those voices were turned against them. The anti-war movement in the Western world prior to 1939, were saying that this type of the appeasement of the fascist forces was ultimately going to lead to war in the West, but they never ever thought that it would. Chamberlain of course came back from Munich with his little paper and umbrella and that was to be the finish of war. But that was only fallacy. But this did abide very strongly and because of the support of the Trade Hall Council here, and the fact that there was some division through the labour movement about it, the church actually entered into the controversy officially.

A BTLC resolution endorsed ‘Beau’ Williams’ view- “that in endorsing English Prime Minister Chamberlain’s actions, the Lyons government was not expressing the opinion of a huge majority of the Australian people” and demanded “that Government support the granting of credit and arms to the Spanish Government.”

In Ballarat the Courier did not take an editorial position on the Spanish Civil War but reported it in detail every day, including this article on Italian prisoners-

The lives of Italian prisoners will be spared, and they will be released at the end of the war and be allowed to go home. The Minister for Education (Senor Jesus Herandez) greeted prisoners, and said they were among fellow-workers, not enemies, and were the victim of Fascist leaders. He added “We have raised the flag of liberty. Cry to your Mussolini that you are going to do the same. The Italians wept and cheered during the speech.

But Franco won the Civil War and ruled Spain for thirty six years, although he never overcame his links to Fascism and Hitler. Franco died in 1975, having restored the monarchy before his death, making King Juan Carlos I his successor, who led the Spanish transition to democracy. After a referendum, a new constitution was adopted, which transformed Spain into a parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy.

The Ascendancy of Fascism

By the end of the 1930s fascism was in the ascendancy in Europe. In August 1938, while Attorney-General, Menzies spent several weeks on an official visit to Nazi Germany and strongly supported the appeasement policies of the Chamberlain Government, believing that war should be avoided at all costs. A BT&LC resolution certainly opposed that view- ‘That in endorsing English Prime Minister Chamberlain’s actions, the Lyons Government was not expressing the opinion of a huge majority of the Australian people.’ But with Lyons' sudden death in April 1939, Menzies was elected leader and war was declared on 3 September 1939. In June 1940, the Menzies Government declared the CPA an illegal organization under the National Security (Subversive Organizations) Regulations. During the period of illegality, the CPA grew rapidly. At the time it was banned, it had 4,000 members, in the next two years it reached 15,000 and 50,000 were reading its illegal press. The circulation of The Catholic Worker edited by Santamaria, which declared itself opposed to both communism and capitalism, was 5,000 a month rising to 55,000 a month in 1940.

The British leaders of the Commonwealth having come to the late realisation that appeasement was not working so Australia was off to another war just twenty years after bearing a heavy cost of that earlier conflagration. In declaring war the words of the Prime Minister Menzies set us firmly back as members of the British Empire- ‘There can be no doubt that where Great Britain stands, there stands the people of the entire British world.’ We had stepped away from the brave and optimistic world of Clara Seekamp in Ballarat in 1855 although another wave of immigrants was coming:

No, the population of Australia is not English but Australian, and sui generis. Any one who immigrates into this country, no matter from what clime or of what people, and contributes towards the development of its resources and its wealth, is no longer a foreigner...The latest immigrant is the youngest Australian.

Compiled by Jennifer Beacham

Resources used in this article-

Ballarat TLC Minutes Ballarat Trades Hall

The Courier

Ed. P Mansfield 1982-3 Ballarat Library project ‘Ballarat and District 1920-1940 An Oral History’

Ross Fitzgerald, Adam James Carr, and William J Dealy. The Pope's Battalions: Santamaria, Catholicism and the Labor Split. Univ. of Queensland Press, 2003.

Shauna. Hurley. “’Catholics, Communists and Fellow travellers: The Ideological Battle in Ballarat 1936-1951,Unpublished BA (Hons.) thesis

Amirah Inglis Australians in the Spanish Civil War Sydney Allen and Unwin 1987